Turning Slack into a network

One of the four big bets in Stewart’s Master Plan was to make Slack a network.

We initially designed Slack to be used for a company’s internal communication. Any company would still have plenty of inbound and outbound communication with the wider world: customers, vendors, contractors, their community and so on. Those messages were the job of emails and meetings and phone calls. Slack was for the people who worked at a company to talk to each other. It was more efficient than the tools it replaced for that kind of work.

As companies began to depend upon Slack and integrate it with their other systems more deeply, and as the number of organizations using Slack expanded into the tens of thousands, a new opportunity became clear. What if companies that used Slack could use it to talk to each other? What if all the benefits of communicating in Slack – channel-based organization, rapid turnaround, shared context, expressive messaging, file and platform integration, archive access – could be applied to the work that happened across organizational boundaries?

The idea snowballed as we imagined the possibilities to provide a centralized venue for the work that happens between a company and its customers, or its lawyers, or its vendors. Or the work that happens between all the various organizations involved in a large complex event like the Olympics or an industry conference. Or between companies brokering a merger or acquisition, or an agency and their clients. Or the thousand other types of relationships companies have with one another.

What if Slack became a network? This was a compelling idea. Stewart had proposed it in one form or another since the early days of the company, but by 2016 the time had come to actually do it. For customers, it would allow even more of their communication and coordination to happen in Slack. For us, it would help build a competitive moat of utility and network effects that we hoped could stave off Microsoft Teams and other competitors.

Shared Channels is the kind of feature that is easy to explain at a high level. Our customers grasped it and understood why they’d want it. It’s just the Slack you know and love, but now you can talk to people at other companies. We didn’t have trouble getting customers and press excited about the feature.

The difficulty with building the product stemmed from two major issues:

- Slack had been built with the assumption that channels (and everything else: people, apps, emojis, files, etc) belonged to only one team, and that all data access was limited at the team boundary. Shared channels changed that deep assumption.

- Consumer network products (think Facebook or Twitter) achieved their viral growth through lightweight open invitations to connect users. Business software has a great deal of built-in resistance to this kind of openness, and significant security and privacy requirements that make it difficult to achieve.

In order to address the first issue, we had to remodel multiple layers of Slack, from the database up to the clients. Similar to how we rearchitected Slack for Enterprise Grid, which introduced the concept of an organization that could contain many workspaces, we had to rethink many of our fundamental assumptions for shared channels.

As Myles Grant, Slack's first Principal Engineer, says:

"That fucker [Shared Channels] broke so many assumptions about how we architected the product. We had gotten so used to just broadcasting any changes to every connected user, which obviously doesn't work from a privacy or scaling perspective when you combine two-or-more teams. There were so many changes to that model that we had to make for shared channels that also ended up being good improvements for scaling the regular product as well."

Channels could now be accessed by multiple teams. This meant we needed to start partitioning Slack data by channel rather than by workspace. A simple way to do this would be to make one team the owner of the channel and allow others to access it as a type of “guest” of the host team. But this wasn’t the product experience Stewart envisioned, nor did it address the various complexities our customers’ real-world organizational relationships entailed.

Instead, a shared channel became a mutually accessed object with a shared history. But on each side of the shared channel (whether one or a dozen teams were sharing it), the channel could have a different name, different levels of privacy, different administrative rules, and so on.

For example, an ad agency Alpha Marketing might have a shared channel with their client Beta Industries. On the agency side, the channel could be public and named after their client: #client-beta-industries. On the client side, it might be private and named after the project: #secret-summer-ad-campaign. This way all participants had the right context and controls around their side of the shared conversation.

Needless to say, all these new capabilities introduced hundreds of wrinkles into our original model of how channels should behave.

Take data retention as an example. Data retention controls allow a company to set rules for how long to keep messages after they’re written. By default Slack keeps messages on paid teams around forever. But many industries and companies have legal and compliance requirements (or simple preferences) for specific durations.

How should this work in a shared channel? Mike Demmer, one of Slack’s principal engineers and a lead on the Shared Channels project, outlines the problem:

Company A has a policy their messages need to be retained for 1 year for compliance. Company B has a policy they cannot be retained for more than 90 days for their compliance.

Now what do you do when they want to share a channel to do a joint project? You can't use either side's policy exactly because it conflicts with the other, plus we wanted things to be simple. So rather than some kind of negotiated agreement, we decided that each side’s messages would be subject to their own policy. Which means that if you look back 90 days in this example, you have a one-sided conversation, but that's better than all the alternatives.

This small example teases the range of considerations that emerged as we started to build out the feature set. Balancing the design goal of a simple and intuitive user experience with the complicated administrative, privacy, legal and compliance requirements of our customers turned out to be an enormous challenge that took several years of effort to fully realize.

By this point in Slack’s history, Stewart had become an immensely busy CEO. Slack was growing rapidly both as a business and as a company. We had major new features coming to market, competition from the biggest software companies in the world, and the growing pressure of a rising valuation. Stewart was at the forefront of all of this.

But Stewart was also still our primary product leader. Of course, many others helped to lead the Product and Design organizations, and hundreds of people helped shape the product. But the buck started and stopped with Stewart on our highest priority product features, including Shared Channels.

For the large product vision, this worked. It also worked for Stewart’s intuition about what the most important facets of the problem were to solve for customers, and the details of the experience we had to deliver for the feature to be widely adopted. Most of all, it worked for Stewart’s unique ability to tell a story both internally and externally about the kind of work we were enabling with the feature.

However, it frayed as the minutiae of reorganizing Slack around shared channels began to manifest with hundreds of small tradeoffs. The team working on the feature was confronted with how to translate the big-picture vision into working software. This meant resolving thousands of considerations that weren’t apparent at the outset.

- How do we make sure that shared channels are labeled for clarity in all our various user interfaces?

- What does a “disconnected” shared channel look like – and can it be reconnected?

- How do we plug these new “externally shared channels” into the emerging complexities of our Enterprise Grid product (which had their own distinct concept of internally shared channels across workspaces)?

- Can a channel start out internal and then become shared later?

- Are platform apps configured by one organization available to all users in a shared channel?

- What profile information should be visible for members of a shared channel?

- What administrative controls would all this entail, and how granular should those permissions be?

And so on. The project ate up product managers, with at least three primary owners over the lifecycle of the project from inception to release. Reams of product documentation were shared and shredded as the project unfurled.

Over the years since we started Slack, we'd all become used to Stewart being highly available and engaged with the myriad thorny product and design issues that came up. But at this point in time, as Slack’s growth continued to accelerate and as we set our sights on more ambitious product opportunities, he only had so much time for each of those key projects. Not to mention managing customers, investors, press, and a large and growing organization.

Sometimes the team was left to guess what Stewart wanted – a notoriously difficult task. Weeks or months could go by without clarity on key product decisions, and without signoff from our busy CEO. This sometimes led to engineering rework and backtracking once a decision was eventually made.

Mike Demmer shares this anecdote in regards to the data retention example above:

This particular decision is the one that when we first talked to Stewart about it, his reaction was something like “Huh? What? Are you guys deliberately fucking with me and wasting my time with this shit?” Needless to say we didn't do a good job of explaining it and later he got on board.

Stewart’s acumen for software design is famously good, and his insistence on control of key projects was appropriate to the scale of the opportunity in front of us. As a veteran design-oriented CEO, this was one of the fundamental strengths he brought to his leadership of Slack.

But we seemed to have grown to the point where no one person could keep up with all the ins and outs of the projects we were doing in parallel, even someone as uniquely talented as Stewart.

This became one of several acute growing pains during this phase of the company. We would have to learn how to scale the unique strengths of our CEO as we expanded the scope and scale of our efforts.

Nevertheless, by late 2017 we released an initial beta of the feature to a limited set of teams, and over the following months continued to expand this set to more and more customers. We wanted to get as much real-world feedback and usage as we could, even though we hadn’t yet ironed out all of the details or built support for all the use cases we imagined.

As ever, users helped point us in the right direction. When something didn’t make sense, they let us know what they expected to happen. When they hit a roadblock, they shouted at us until we could remove it. This was our favourite way to work: learning directly from our opinionated, impatient, treasured customers about how to make Slack awesome for them.

And of course, we gathered this feedback via shared channels. Following our deep commitment to dogfooding, we used our just-working-well-enough, very-much-under-construction new product feature to gather feedback directly from our customers. This had the massive benefit of making us use the feature on a daily basis, allowing us to notice bugs and rough edges as we went.

As we gained confidence, we were able to add support for requested use cases, such as private shared channels, multiparty shared channels, and eventually enterprise grid support.

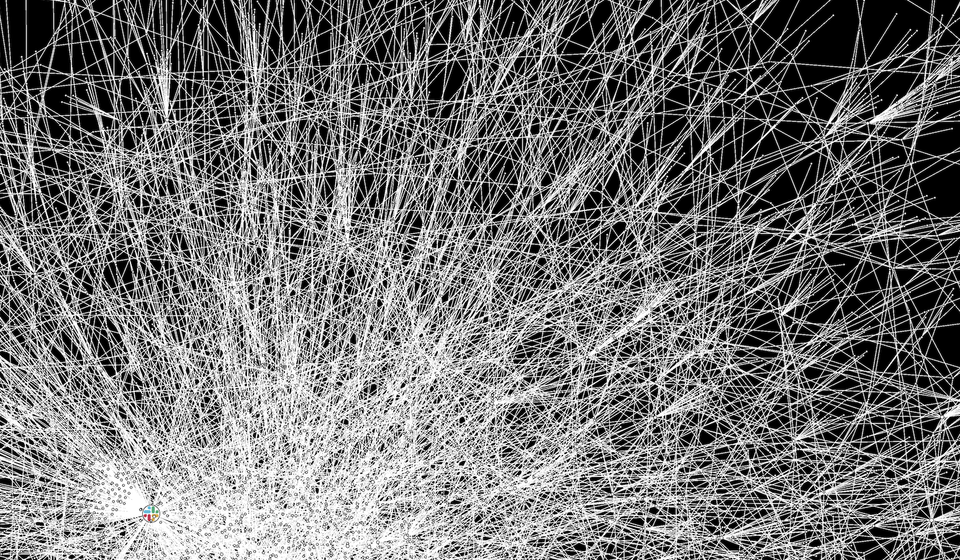

As the beta product found its stride, the network began to grow. Early adopters, intuiting the value of the network, created connections freely. They pulled in other organizations from their orbit, adding shared channels for every project, relationship and discussion where it was useful.

Others, however, balked at the free flow of information. What, exactly, would be shared? And by whom and for how long? Was this compliant with the various privacy and security requirements for each organization?

In the latter case, an extended set of administrative controls, invitation visibility and expiry, and channel management features became necessary. The requirements for many customers and industries meant that the desired simplicity of an email invitation to join a shared channel would not be possible. This became an ongoing balancing act, with a simple and understandable user experience enabling quick connections on the one hand, and a product that complied with the array of controls and requirements of our most valuable customers on the other.

Again from Mike Demmer:

I don't know if it was possible to actually thread the needle perfectly, but at times we were too cautious, then we tried to open up more, at one point got some twitter storm and rolled back quickly, then we added more enterprise controls, etc etc. But in general I think it's a really hard problem to try to jam a social-style invitation thing into a team-based business product.

Slack network connections in shared channels, 2017-2019

After nearly two years in beta, Shared Channels was finally released in 2019, branded as Slack Connect. Stewart was extremely bullish on the prospects of our new product:

I’ve been making network-based software for a living for the last 20 years. Over that time I’ve worked on a lot of great projects directly, and have seen many more from the inside, as an investor, board member or just as a friend. I have never been more excited about a product or its product market fit than I am about shared channels.

The success of Shared Channels became one of the central storylines of Slack's trajectory as we prepared to take the company public.

- Thanks to Mike Demmer, Myles Grant and Sean Rose for their notes on this post.

- Three years later in 2022, Microsoft copied the feature and released a preview of it. It was named “Microsoft Teams Connect Shared Channels” – you really cannot make this stuff up. In 2025, they still have significant limits on their version – supporting up to 50 teams and up to 5,000 members, compared to Slack’s support for 250 teams and an unlimited number of members. Of course, Microsoft gave away their version for free.