The 800-pound gorilla

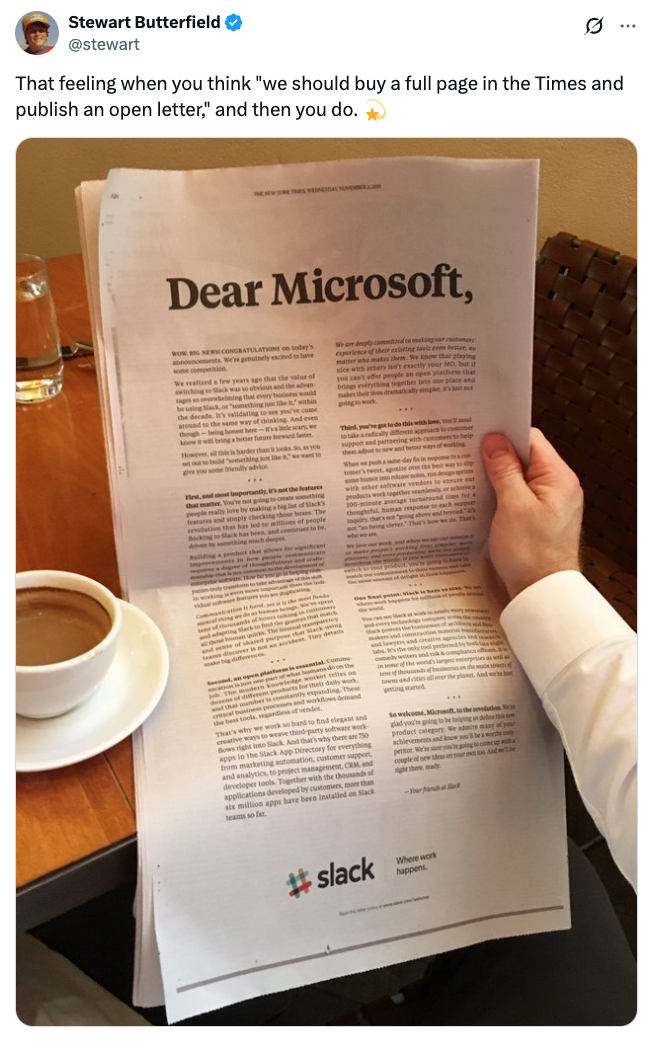

On the morning of November 2nd, 2016 we arrived to the office to find a paper copy of the New York Times on our desks. In it was a full-page ad welcoming Microsoft to the market that Slack had created. Not coincidentally, Microsoft would announce the launch of their new product “Teams” that day.

Stewart drafted the ad the week prior in one of the 4th floor meeting rooms in our Vancouver office, revising the copy until it felt right. The company was not typically in the business of buying expensive newspaper ads, but the circumstances were unique. It’s not every day that the biggest software company in the world launches a clone of your product. We did not intend to take the news sitting down.

The full letter was simultaneously published on our website (archived now). It read:

Dear Microsoft,

Wow. Big news! Congratulations on today’s announcements. We’re genuinely excited to have some competition.

We realized a few years ago that the value of switching to Slack was so obvious and the advantages so overwhelming that every business would be using Slack, or “something just like it,” within the decade. It’s validating to see you’ve come around to the same way of thinking. And even though — being honest here — it’s a little scary, we know it will bring a better future forward faster.

However, all this is harder than it looks. So, as you set out to build “something just like it,” we want to give you some friendly advice.

First, and most importantly, it’s not the features that matter. You’re not going to create something people really love by making a big list of Slack’s features and simply checking those boxes. The revolution that has led to millions of people flocking to Slack has been, and continues to be, driven by something much deeper.

Building a product that allows for significant improvements in how people communicate requires a degree of thoughtfulness and craftsmanship that is not common in the development of enterprise software. How far you go in helping companies truly transform to take advantage of this shift in working is even more important than the individual software features you are duplicating.

Communication is hard, yet it is the most fundamental thing we do as human beings. We’ve spent tens of thousands of hours talking to customers and adapting Slack to find the grooves that match all those human quirks. The internal transparency and sense of shared purpose that Slack-using teams discover is not an accident. Tiny details make big differences.

Second, an open platform is essential. Communication is just one part of what humans do on the job. The modern knowledge worker relies on dozens of different products for their daily work, and that number is constantly expanding. These critical business processes and workflows demand the best tools, regardless of vendor.

That’s why we work so hard to find elegant and creative ways to weave third-party software workflows right into Slack. And that’s why there are 750 apps in the Slack App Directory for everything from marketing automation, customer support, and analytics, to project management, CRM, and developer tools. Together with the thousands of applications developed by customers, more than six million apps have been installed on Slack teams so far.

We are deeply committed to making our customers’ experience of their existing tools even better, no matter who makes them. We know that playing nice with others isn’t exactly your MO, but if you can’t offer people an open platform that brings everything together into one place and makes their lives dramatically simpler, it’s just not going to work.

Third, you’ve got to do this with love. You’ll need to take a radically different approach to supporting and partnering with customers to help them adjust to new and better ways of working.

When we push a same-day fix in response to a customer’s tweet, agonize over the best way to slip some humor into release notes, run design sprints with other software vendors to ensure our products work together seamlessly, or achieve a 100-minute average turnaround time for a thoughtful, human response to each support inquiry, that’s not “going above and beyond.” It’s not “us being clever.” That’s how we do. That’s who we are.

We love our work, and when we say our mission is to make people’s working lives simpler, more pleasant, and more productive, we’re not simply mouthing the words. If you want customers to switch to your product, you’re going to have to match our commitment to their success and take the same amount of delight in their happiness.

One final point: Slack is here to stay. We are where work happens for millions of people around the world.

You can see Slack at work in nearly every newsroom and every technology company across the country. Slack powers the businesses of architects and filmmakers and construction material manufacturers and lawyers and creative agencies and research labs. It’s the only tool preferred by both late night comedy writers and risk & compliance officers. It is in some of the world’s largest enterprises as well as tens of thousands of businesses on the main streets of towns and cities all over the planet. And we’re just getting started.

So welcome, Microsoft, to the revolution. We’re glad you’re going to be helping us define this new product category. We admire many of your achievements and know you’ll be a worthy competitor. We’re sure you’re going to come up with a couple of new ideas on your own too. And we’ll be right there, ready.

— Your friends at Slack

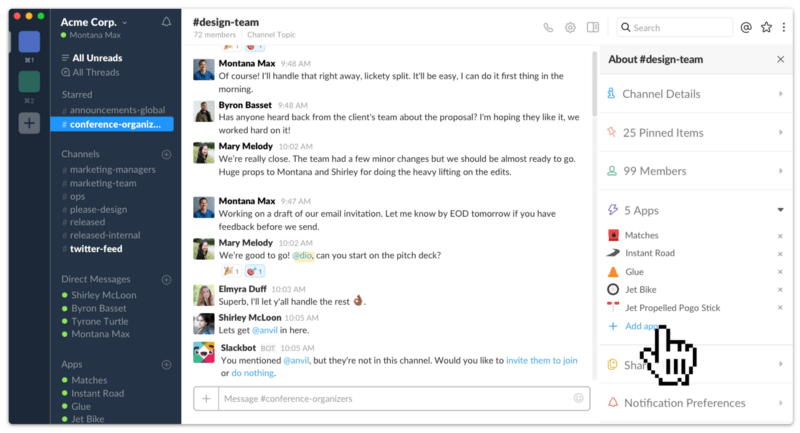

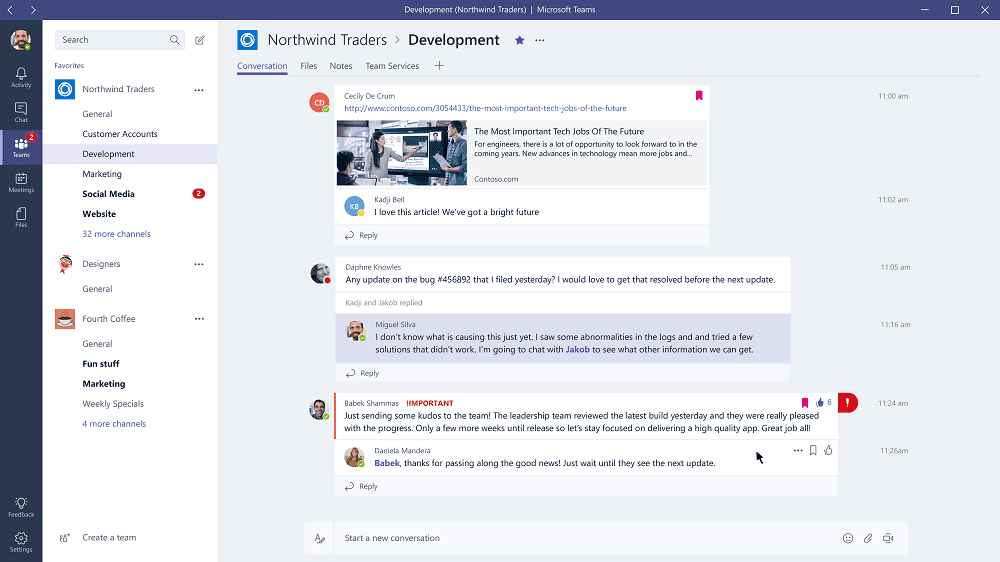

Microsoft Teams cloned Slack’s core featureset of topic-based channels and plugged it into the Office 365 suite of software that included email, calendars, and documents. In prior announcements, Microsoft had telegraphed to the world and their customers that this was coming. Slack had begun to disrupt their core customer base of business users, shifting workflows from email to messaging interfaces and realtime systems. By stealing that attention, Slack threatened one of the crown jewels in the Microsoft empire.

They wasted little time copying Slack. At this point we had a few hundred engineers. Microsoft had tens of thousands. And they had our app as a blueprint for what worked. Instead of finding a path to the product as we had through prototyping, iteration, and refinement with customer feedback, they could simply copy our features.

Reports from insiders at the time suggested that existing Microsoft software Sharepoint (an intranet management and file-sharing tool) had been hastily repurposed and layered under a chat-based interface to create the new product. The result was slow and clunky and had serious limitations to its scale (even now Teams has drastically lower limits on core features like number of users per channel and number of channels per team), but it at least looked like Slack and offered the same core utility of instant company-wide messaging.

Slack and Teams in 2016.

With the public letter, Stewart sought to set the terms of engagement on which we would battle the giant software company. Specifically, on the quality of the software, the openness of the platform, and the attention which we paid to customers. He did it with his distinctive mix of earnestness, wit, and debate-team argument. He did not want Microsoft to dictate these terms, nor for Slack to be swept aside by the arrival of a 40-year old incumbent player in the industry. The media narrative around such competitions often defines how people feel about them. Stewart's letter told our side of the story.

As far as getting attention, it worked. On the day that Microsoft hoped to own the news cycle around enterprise collaboration software, Slack ended up being mentioned prominently in just about all of the coverage. With his usual knack for unusual PR, Stewart had managed to co-opt Microsoft’s announcement to suit Slack’s ends. For those who had not yet heard of us, it introduced Slack as the scrappy upstart who was already in a leadership position against a giant everybody knew. We were David and Microsoft was Goliath. And who doesn’t like an underdog story?

But there was also significant blowback. Many found the tone of the letter condescending or insincere. Others felt it was foolish to invite direct conflict with a company known to be ruthless in their treatment of threats to their empire. The general mood of buoyant optimism around Slack had cooled slightly by this point, and this tipped many industry observers from enthusiasm to skepticism about our prospects. To earn our seat at the table, we had better figure out how to compete with the most powerful companies in the world. This letter didn’t bode well from their perspective.

Alongside the growing pressures of our business scale and the internal challenges of our rapid increase in company size, this marked a shift from the lighthearted positivity of the first few years toward something more mature and complicated.

Internally, there were mixed reactions to the ad. Some employees and a large swath of the sales staff found it galvanizing. It was good to directly identify and fight an enemy. Competition is a wonderful motivator, and a way to instil the urgency and determination needed to succeed at our newfound scale. We were finally in the fight we always knew was coming. “Let’s fucking go!” was a common refrain of those who found the memo energizing.

Others inside the company were confused. Hadn’t we always said we were “competitor-aware, but customer-obsessed”? Did this serve customers? Or was it a distraction? Was it a good idea to publicly provoke such an infamously anti-competitive and vicious rival? Wasn’t our software better than theirs – and couldn’t we compete on those terms without explicitly inviting a fight?

And who used Microsoft anyway? We built on Macs (with the notable exception of our Windows-dedicated CTO) and deployed on Linux. Most of our early customers in tech and media, like us, used open source tools and "best of breed" software (a shorthand for cherry-picking the best tools for the job rather than purchasing a corporate software suite). Very few used Microsoft software. This would turn out to be a reasonably large blind spot for many rank and file staff at the company in the years to come.

But all those varying reactions mattered little as Teams entered the market over the following years. Two things actually mattered:

- Teams was free. There was no way to pay for it even if you wanted to. In many cases you got it whether you wanted it or not if you were a Microsoft customer, with it being auto-installed as part of regular software updates (and then force-reinstalled if you deleted it).

- Teams came bundled with Office. It replaced “Skype for Business”, Microsoft’s voice and video calling service, and came attached to the popular Office 365 suite which a huge percentage of companies were already bought into.

Teams was less feature-rich than Slack (and those features didn’t work as well), its platform was narrowly focused on Microsoft’s own ecosystem of tools, and it was certainly not made with love. On these terms Slack was demonstrably better. But Microsoft had been at this game for decades, was entrenched across industries, and had the most valuable distribution network in the software industry.

As Ben Thompson of the influential Stratechery newsletter later observed in 2020:

The obvious reason for Teams’ success relative to Slack is the oldest tactic in the book: Teams is free, and Slack isn’t. Well, technically, Teams requires an Office Microsoft 365 subscription (although yes, there are free versions of both Teams and Slack), but as Slack itself notes, a good portion of its addressable market has exactly that. In other words, the effective choice is exactly what I stated: “free” versus paid.

Moreover, while Slack concluded its advertisement by talking about how difficult it would be for Microsoft to convince Slack users to “switch” to Teams, switching was never the goal: just as Facebook created Instagram Stories to remove the impetus for new users to even try Snapchat, Teams is particularly effective as a way to prevent a Microsoft customer from even trying Slack. And, in that case, it doesn’t matter how much “love” Slack put into its product: said love was not simply unrequited, but unexperienced.

Microsoft used their fundamental advantage as an incumbent software leviathan to bypass the terms on which we wanted to fight them. With very few exceptions, they didn’t steal our customers. Our customers loved Slack. But they tapped the massive market they already had and greatly reduced our chance to ever reach them. A company that was already paying a steep premium for the essential tools of Office 365 got Teams “for free” and it seemed fine to them. The inertia at play in this scenario made it very difficult to move such a company to pay for an additional tool in the messaging niche. Having a better, more open product made with love wasn't enough.

The 800-pound gorilla had used its market dominance and distribution advantage to box us in to our existing customer base. Stewart would later remark that in the years after the letter Microsoft seemed, “Unhealthily preoccupied with killing us,” even after the features of Teams shifted to focus on voice and video calls and away from Slack's core value proposition.

After reportedly entertaining an internal campaign to acquire Slack for $8,000,000,000, Microsoft instead decided to do what they do best: eliminate competition with the help of their massive market dominance. People by-and-large disliked Teams, but it was right there on their desktop, and their IT administrator got it for free.

Despite the competition, Slack would go on to enjoy rapid growth over the following two years, tripling from 4 to 12 million daily active users (huge numbers in enterprise software for a new tool). In the same time period, Microsoft would report growing from zero to 115 million users. When a piece of software is free, installed by default, and bundled with your most popular software, it’s hard to judge what 115 million users really means, but it drove home the point. Microsoft was not going to play on our terms, and more people would use Teams by default than we could hope to reach on our own merits.

At the risk of telling the story out of order, it’s worth noting that Slack would eventually file and win an anti-trust suit against Microsft in the EU. Filed in 2020 and resolved in 2024, the suit alleged that Microsoft had used its monopoly power to bundle Teams into the Office suite and give it away for free, thereby undercutting competition and unfairly skewing the market in their favour. In response, Microsoft has agreed to unbundle and charge for Teams.

It will likely also be subject to fines. However, these fines appear to be considered a cost of doing business. Microsoft has already paid $2.4 billion in EU antitrust fines in the past decade for bundling products. It is not clear that this is a sufficient deterrent when their strategy to eliminate competition clearly works, and the profits from such behaviour vastly outweigh the minor inconvenience of a few billion dollars in fines (to a company with a nearly $3 trillion market cap).

Unfortunately, an eight year lag time between the impact of monopolistic behaviour and the court-ordered correction of that behaviour is of little use to a startup trying to make the leap into the big leagues. There’s no turning back the clock.

At Slack back in 2017-2018, as Microsoft’s competitive pressure was growing, we had other challenges keeping us busy. The newfound scale of our company and the accompanying burden it was placing on our code and infrastructure represented a clear and present danger to our continued success. If we didn’t resolve the existential engineering crises we were facing, we’d never get a chance to fight Microsoft or anyone else.