The week the world changed

In January 2020, a nasty bug swept through our NYC office. Everyone got sick at once and was off for weeks. An uncommonly terrible cold? Some sort of wicked flu? Whatever it was, it knocked our team out.

We didn’t think too much of it on the west coast. Our San Francisco and Vancouver teams were heads down finalizing the scope and rollout plan for our new design. After spending the fall and early winter solving the myriad problems that had cropped up with Slack’s overall design, the late winter was spent solidifying our new one.

Almost every screen of our desktop and mobile apps was changing to align with the new navigation scheme, information hierarchy and UI treatments. The new features we were releasing with the design update were being put through their paces by the QA team and translated by our localization team. Our customer support team was preparing for the inevitable tsunami of feedback and questions they would receive, and updating the hundreds of Help articles that detailed how every part of Slack worked. There sure was a lot to do.

It got done, team by team, one screen at a time. We were living on the new design internally, continuously finding and refining the rough edges we’d missed. Dozens of our customers were beta testing it. To our delight, they seemed to really like it.

It was time to release. We went about planning methodically.

- Did we have instrumentation in place to make sure our changes were having the desired effect? Were we certain we could detect regressions in performance or utility?

- How would we tell the story to the press and to our customers? What would success look like?

- Did we have the right mechanisms in place to halt or revert the rollout if something went wrong?

- How should we handle the rollout across users with multiple workspaces? Could we make sure that once one of their teams got the new design, they all would? Or should we do the opposite and wait until all of your teams had it before turning it on for any of them? We didn’t want anyone to have two versions of the design at the same time across their teams.

- How could we make sure that admins at our customers were not surprised by the changes, and that we equipped them to update their own internal documentation and processes?

- What areas of the design might we be willing to adjust course on based on feedback, and which were non-negotiable? It was better to have consensus on this ahead of wide release to avoid reactive changes under the pressure of critical feedback.

These and hundreds of other questions were considered while we finalized the practical engineering and design details of our updated apps. It was a full company effort. All hands on deck.

We were excited to get the new design out. We loved it internally and wanted our customers to have it. We were also very anxious. Redesigns can be received extremely badly if rolled out clumsily. They can damage the product, the brand, and the business all at once.

We understood the responsibility our customers had granted us to take care of their company communication, and meant it when we said our mission was to make their working lives simpler, more pleasant, and more productive. We knew that it was up to us to maintain the trust and goodwill of our customers, and help them transition to our new design smoothly.

After months of sustained company focus and effort, we were ready. We targeted March 18th to begin the rollout of our new and improved “V2” of Slack.

The novel coronavirus

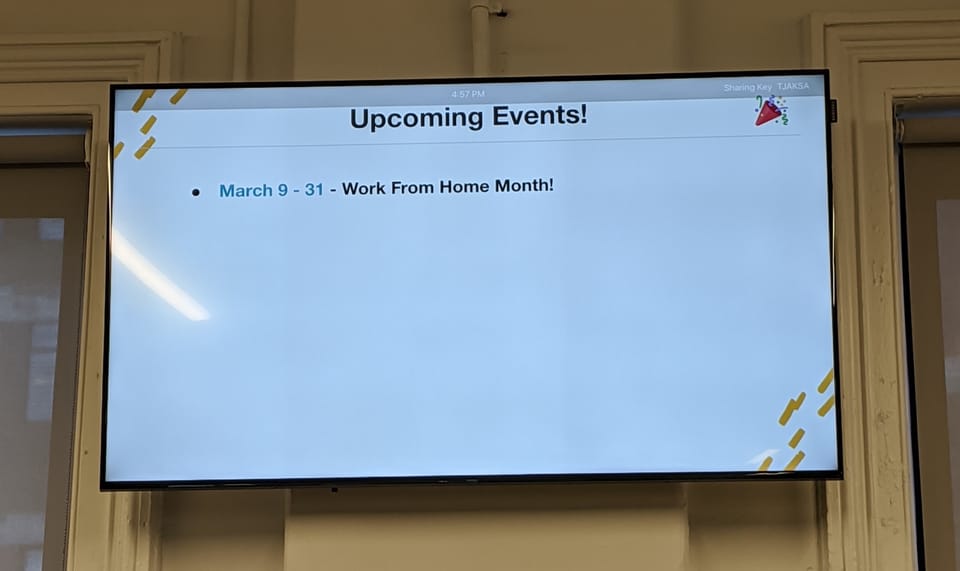

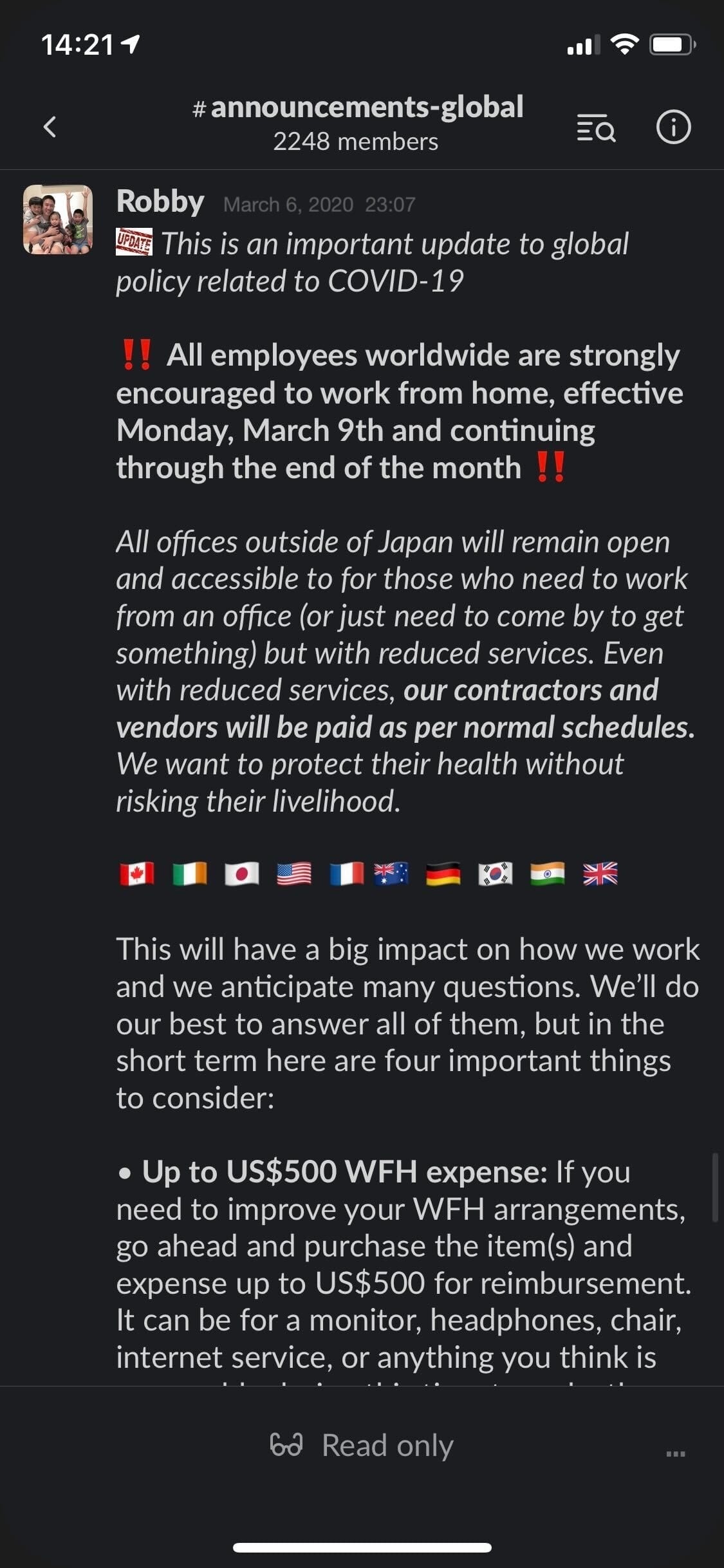

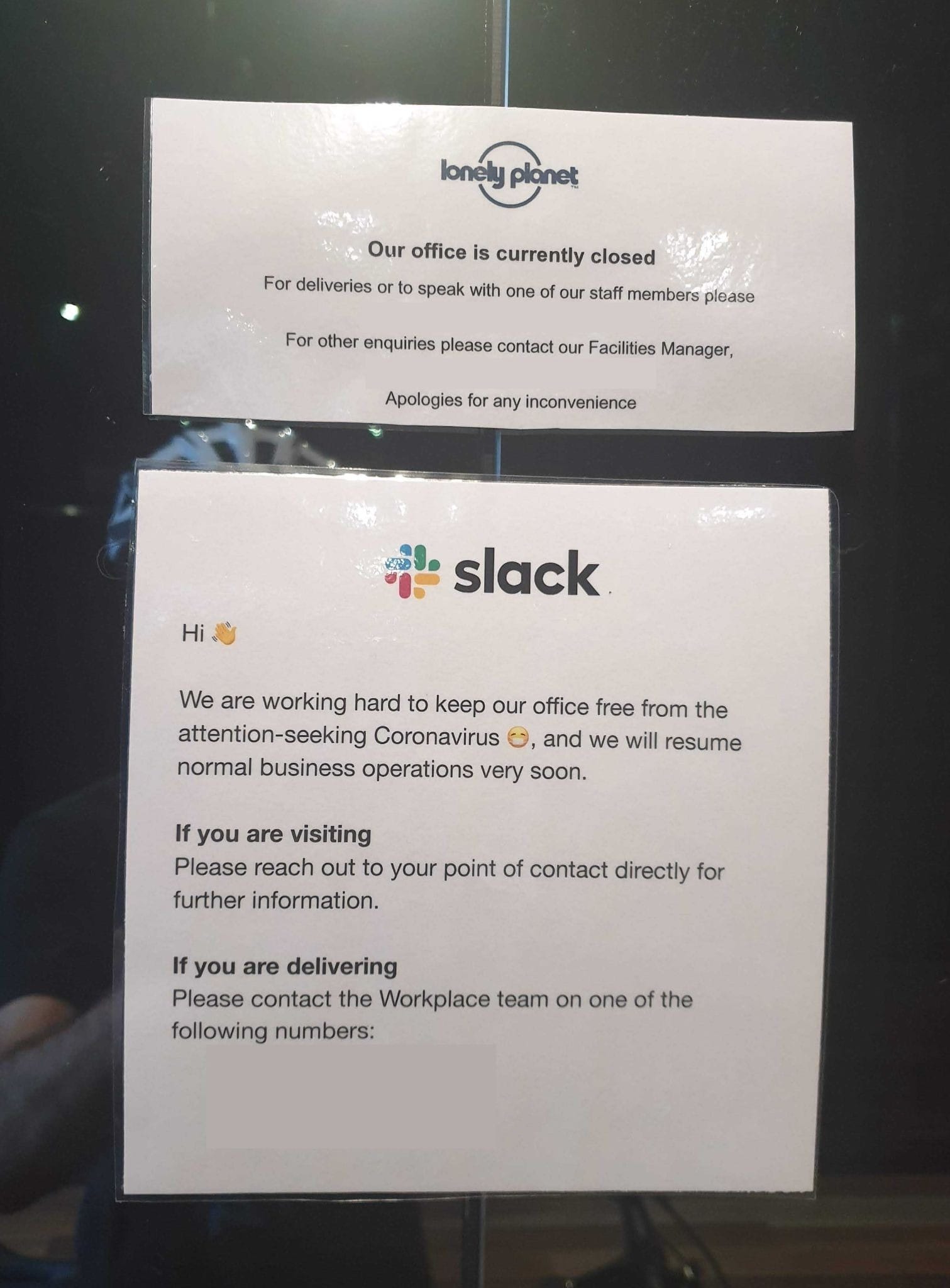

The news was filled with stories about a new virus sweeping across the globe. After initial spikes in China, Japan, Korea and Italy, the novel coronavirus COVID-19 had spread from Asia and Europe to North America. After shutting our offices in Japan, our facility managers and company execs made the decision to strongly recommend everyone work from home starting March 9th. On March 12th this was strengthened to a temporary closure of Slack’s offices and the requirement that everyone work from home.

We had offices around the world, but it was our NYC, Vancouver and San Francisco offices where our product, design and engineering teams primarily worked. Our planned get together in New York for the team to roll out the project in person was canceled. We would be working from home as we sprinted the last mile toward release.

I spent an extra day working in the empty Vancouver office, somewhat exasperated by the interruption to the project we were trying to ship. Were we really shutting down the offices for a cold, I wondered? How bad could it be?

Marg Hernandez, our office manager in Vancouver, was also there closing things down for the initially anticipated 2-week hiatus. Marg was a beloved member of our YVR family, tirelessly taking care of the office and our staff, dealing with whatever came up and keeping everything running smoothly.

In mid-March of 2020, Marg was in the middle of marshalling our Vancouver office’s move from our original home in Yaletown to a newly renovated space in the financial district. We had outgrown our old place, a converted warehouse dating from the early 1900s, and were moving downtown to take over two floors of a plush modern tower. We were scheduled to move in on April 1st. Now she had an unexpected office closure to deal with in the middle of that schedule. I wasn’t the only one frustrated by the interruption to our work.

After tolerating me for the day, she fixed me with her trademark “I will no longer put up with your bullshit” stare and told me, with love, to go home. I sheepishly carried my office chair out with me. I didn’t have one at my house.

Going remote

We switched our meetings from the office to Zoom calls. As a multi-office, highly digital company, the sudden switch to a fully remote workforce was less disruptive than it was to many others. Slack, the product, was already where our company worked. We were all used to communicating via Slack and dialing into meetings in other offices. We were just doing it from home now.

Except.

Except we were at home with our kids. And our spouses or partners who were also suddenly working from home. And maybe extended family and elders who needed support. And the playgrounds and schools were closed. And people we loved were getting sick.

The news was a neverending confusion of new information and changing stories. On social media, misinformation and conspiracies proliferated. Guidance from our local, regional and national governments wasn’t aligned, leaving people with unanswered questions, anxiety and anger. Masks were sold out. Groceries were running low as people hoarded essentials.

We all learned the new protocol of social distancing. There was no clarity on when or if a vaccine would arrive – the fastest vaccine to market before COVID-19 was 4 years and the best guess at the time was that a 2 year cycle might be possible.

Guidance from the company, beyond closing the offices, was to prioritize our own health and safety. To take breaks, and take time off if we got sick. Stipends were quickly set up for everyone to order what they needed for a comfortable work environment at home: external monitors, standing desks, noise-canceling headphones and the like.

It was understood that people’s schedules would be unpredictable, as everyone tried to adjust to a world in which they were working from home full time while supporting their household through a rapidly changing new normal.

Dolly Parton’s famous 9 to 5 schedule became the widely meme'd crazy-making fragmentation of “Working 6-6:45, 8:30-9:15, 11-2, 4-4:07, 7:20-10:45” as working parents juggled children and jobs and the overwhelming disorientation that the pandemic brought to our lives. Others living alone faced the agonizing boredom and loneliness of an interminable absence from the office and their daily social routines.

We joked, darkly, that we weren’t working from home. We were living at work.

The surge

Of course, everyone else was in the same boat. Over the course of a couple weeks everyone in the world who had a desk job became a remote worker. Companies that had already been using Slack began to use it very, very heavily. Companies that didn’t use Slack or Microsoft Teams were suddenly forced to learn how to use them.

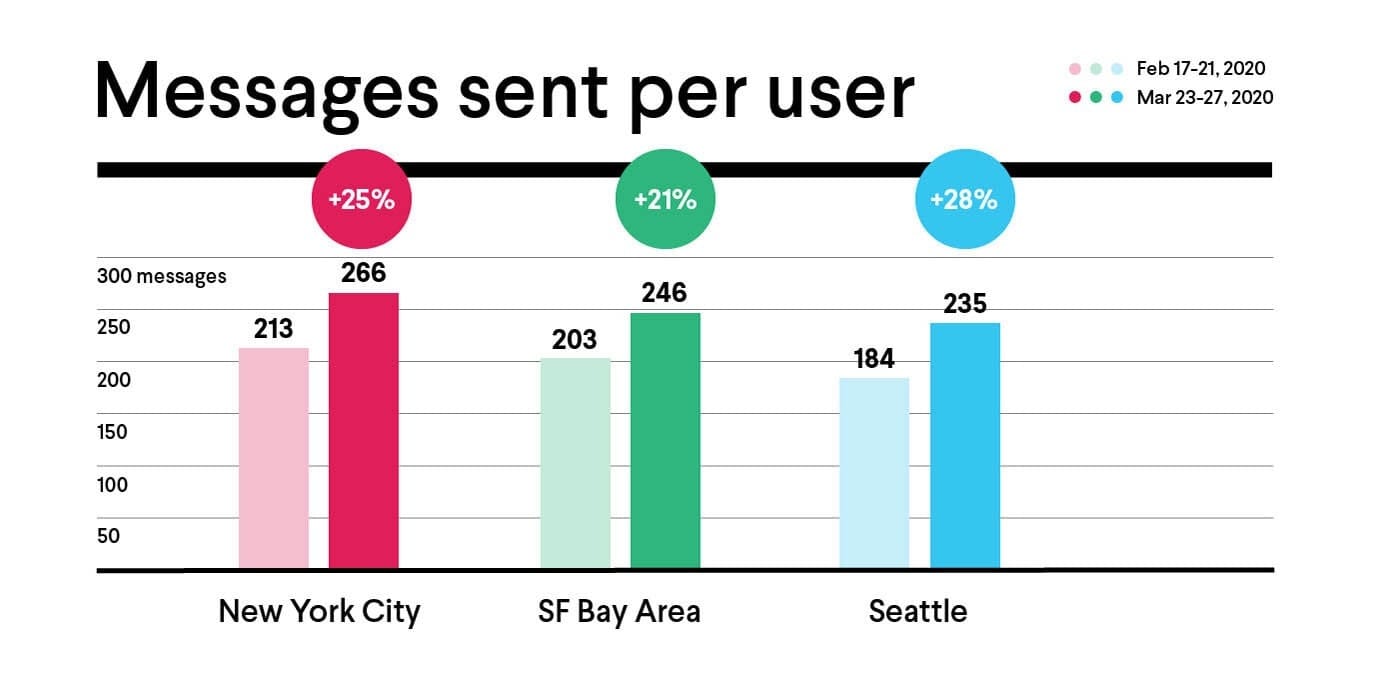

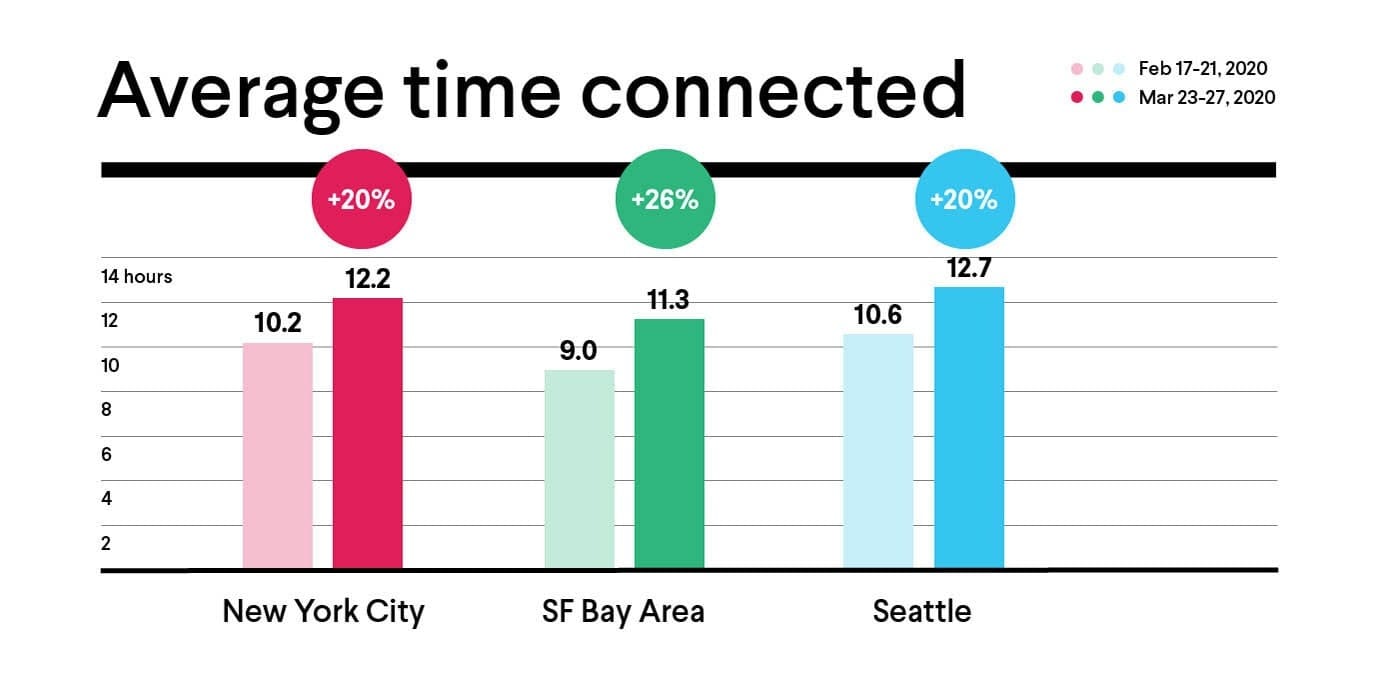

Our stats all spiked: new teams, new users, and volume of activity all surged. Every record we had was shattered on an hourly basis.

Everyone needed what we had built. Slack has always supported distributed and remote working. It was how our own company was arranged when we started it, with people spread across cities and timezones. And our company in 2020 was a perfect example of the kind of internationally distributed workforce that made up the information economy. Slack the product was ideally suited to supporting this mode of work.

Now every company was a remote company, and our stats showed it.

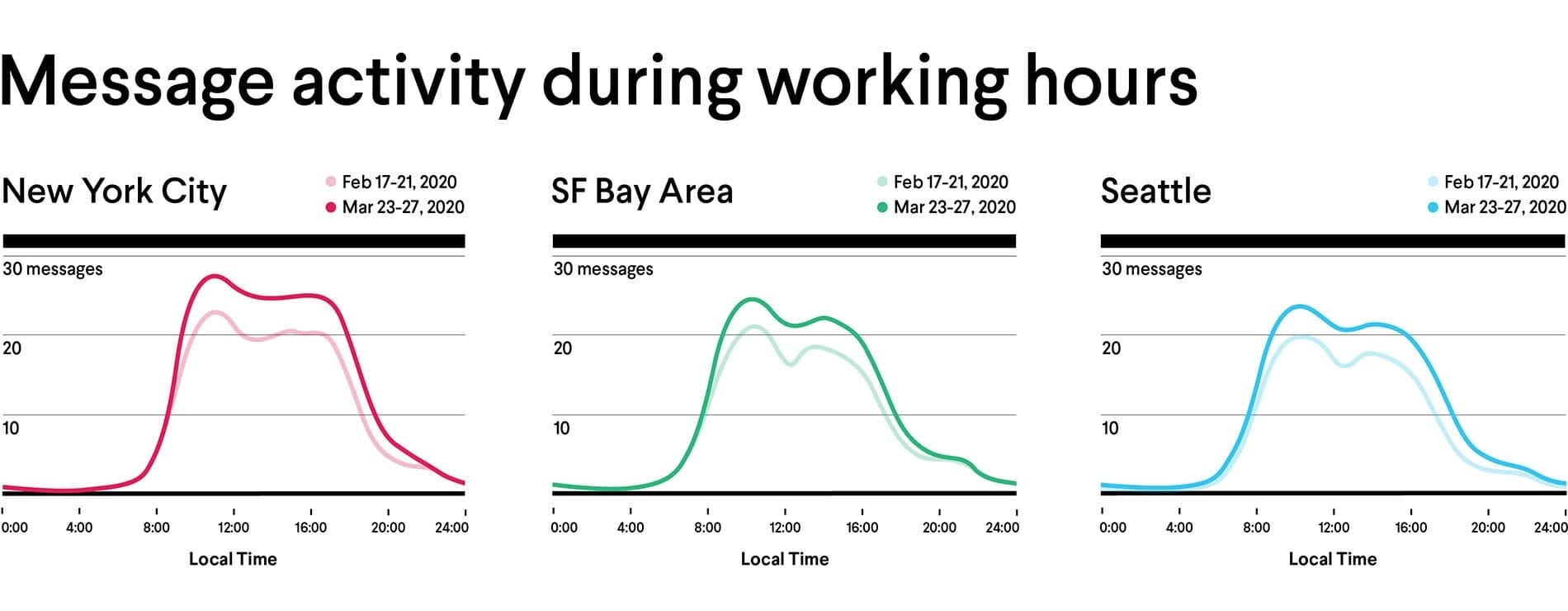

They also showed the first glimpse of what remote work was doing to people’s lives. Despite all of the uncertainty, interruption, and distraction of the burgeoning pandemic, people were still working, and they were switching time spent in the office to Slack. They spent more time connected to their workplace conversations, sent more messages, and extended their workday earlier and later in the day and over lunch. Our best guess was that this remote activity was replacing work that had previously happened in person.

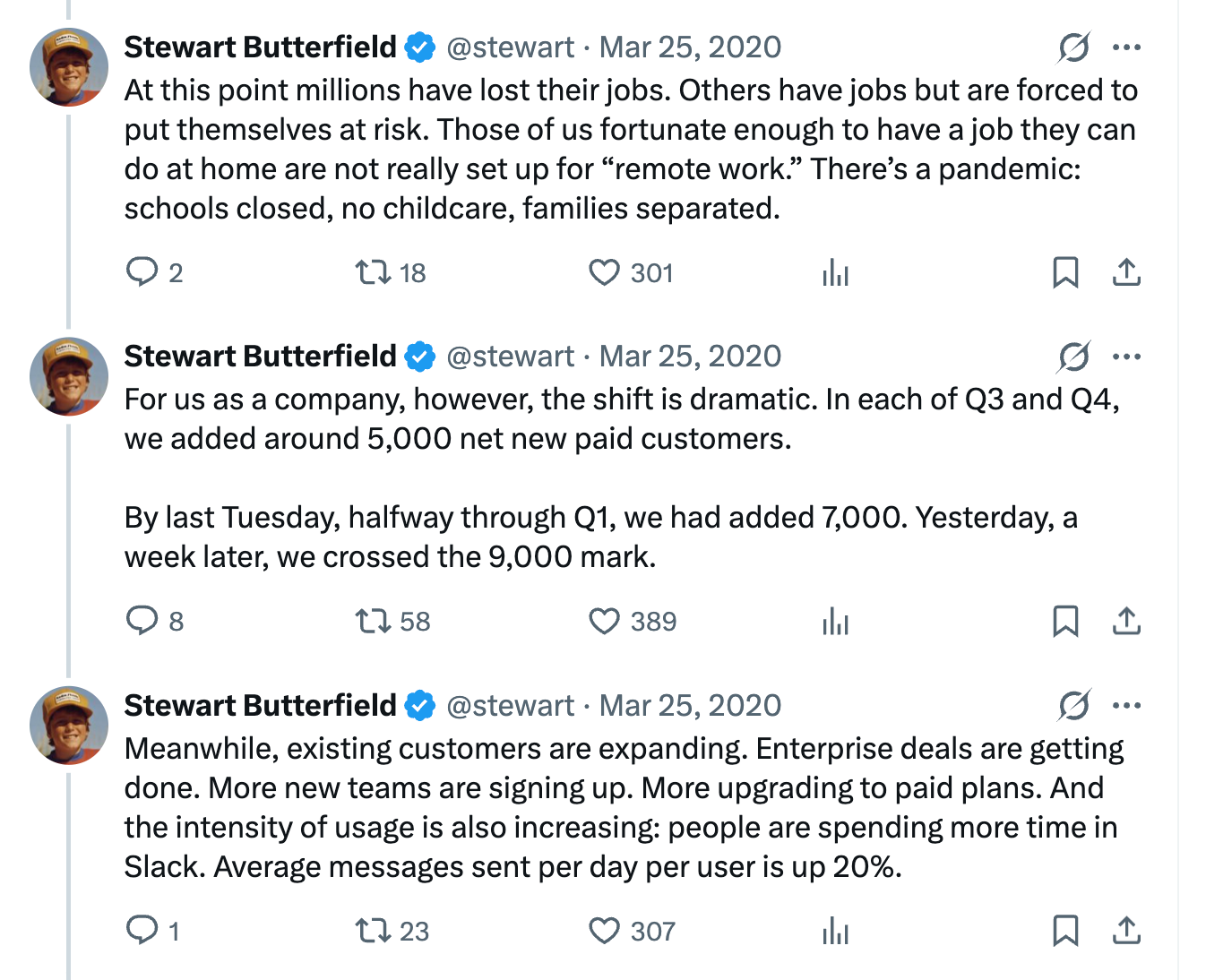

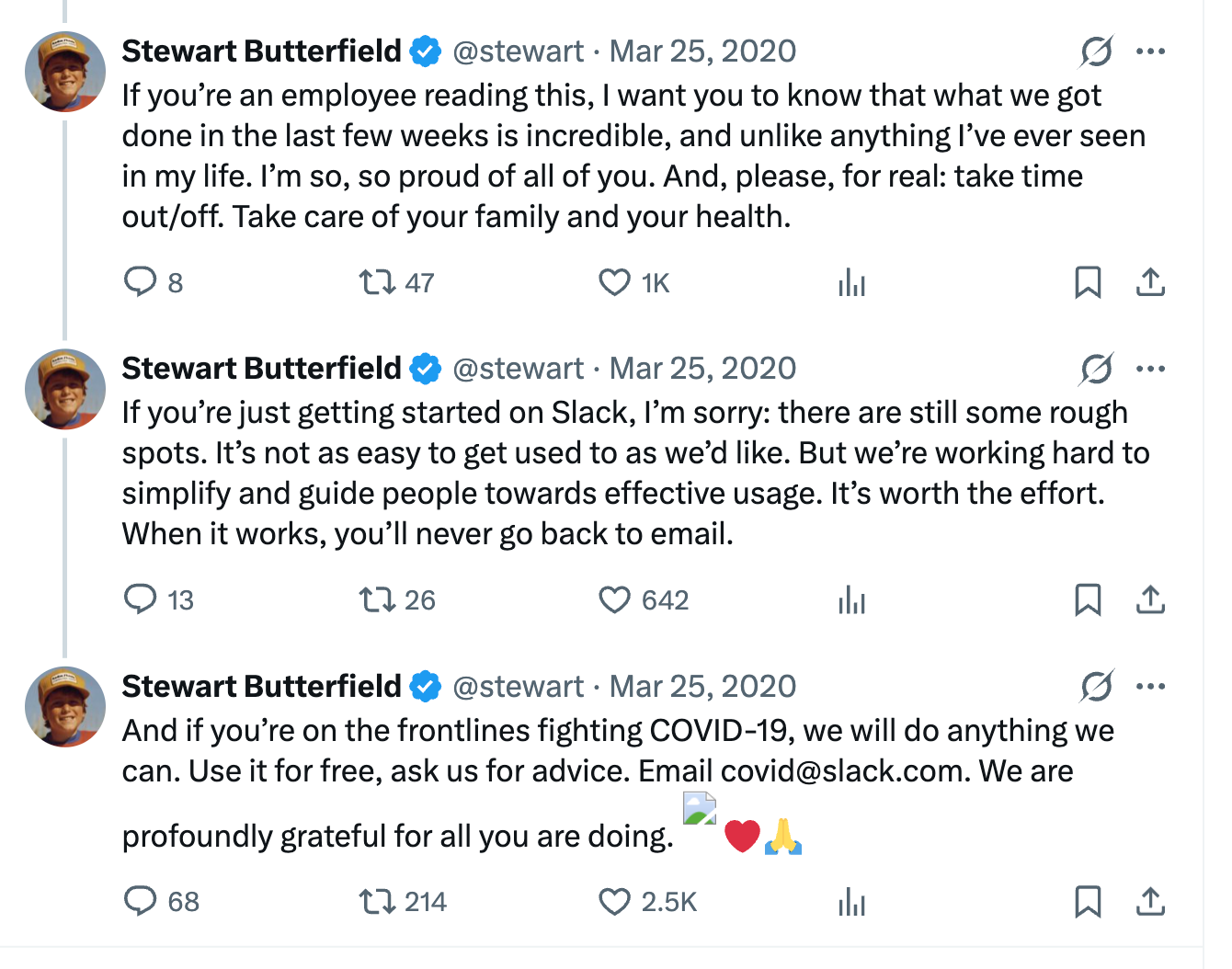

Stewart, who was leading our own company’s sudden switch to an all-remote workforce, was also due to provide guidance to the market on our quarterly earnings call in March 2020. He did so, then shared his experience in a long, characteristically humane thread on twitter.

He was in a paradoxical situation: forced to grapple with the appalling human costs of the virus and its economic fallout, while also recognizing that Slack was the tool people needed to continue working. It was a golden business opportunity wrapped in an unfolding disaster that none of us had asked for. How should he guide the market in this situation?

Stewart recognized the pandemic as an extreme and abrupt example of the kind of disruptive force that demanded organizational agility and adaptation. This had been the core of Slack’s value proposition for years – that by centralizing and streamlining their communication, companies could more rapidly respond to new information, make decisions, and reorient to the situation. That was being showcased before our eyes.

He offered free use of Slack to anyone working on COVID research and relief. This policy was flexibly and generously applied to anyone who asked. The journalist and volunteer-driven COVID Tracking Project was run on Slack, collating and releasing information that was slow to come from governmental sources. It became the definitive source of information in the US during the first year of the pandemic.

In a time that demanded leadership, our CEO was up to the task.

A redesign, now?

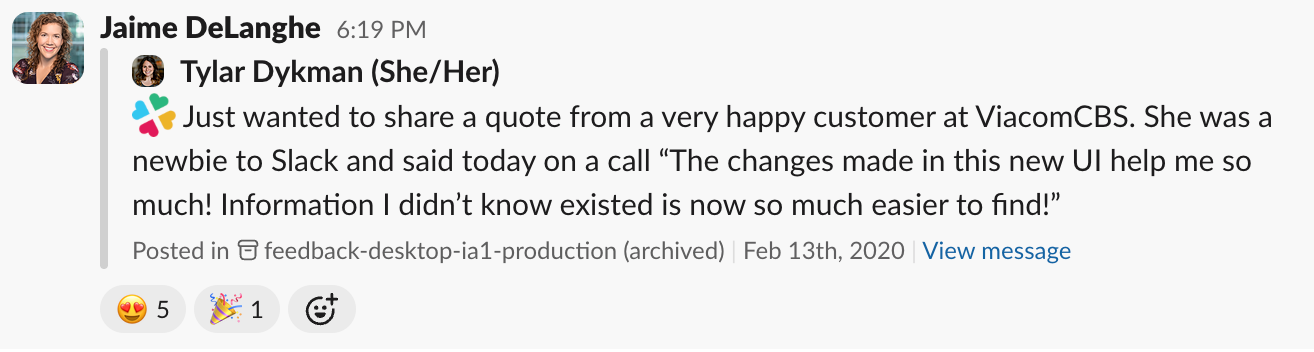

As we neared the planned rollout of our new design, we were listening closely to the beta customers who were using it. What we heard was good. They preferred the new design, noting its ease of use, efficiency and their love for the new additions like sidebar organization. Our metrics showed that they were having an easier time configuring and using Slack’s many features.

We had run a multi-week rollout to new teams in India in February and confirmed at scale that we were on the right track. The improvements to comprehension, discoverability and usability that were core to our efforts had paid off.

Our original rollout plan was conservative, designed in the innocent days before a global pandemic. We would start turning on the new version of Slack for a small percentage of existing teams and a slice of new teams. Our experimental design was based on specific cohorts of users that we could collect data from for a few weeks to confirm that we hadn’t missed anything egregious before rolling it out more broadly.

We were a public company now, and sudden drops in key metrics like conversion from free to paid teams or customer satisfaction would mean real consequences for our company and our shareholders. We used to yolo out new features whenever they were ready. Now we had higher stakes and more pressure.

But we were also seeing an unprecedented spike in expansion and growth. Thousands of new teams were signing up, and hundreds of thousands of new users were being added daily. All of these people were getting the old Slack. The overstuffed, confusing, creaky Slack. The Slack that we knew was causing frustration and disorientation.

Millions of new people started showing up 10 days before we planned to launch the new design. They came looking for a new way to work in the wake of a massive emergency that ripped us all out of our routines and into the unknown. We needed to give them our best.

Jaime DeLanghe, Ethan Eismann and I discussed it briefly, then took the proposal to Tamar Yehoshua, Ali, Stewart, and Cal. Since our company had been using the new version for months, and since our execs already knew that early feedback was positive, we didn’t have much convincing to do. Tamar made the call to immediately turn the new version on for all new teams. We would lose the ability to analyze new cohorts against one another, but our new customers would all get what we felt was the best experience.

For existing teams, the picture was slightly more complicated. We had agreements with hundreds of customers on rollout timing (general timing for paid customers and specific dates for certain large enterprise customers). We would do more harm than good by surprising them with a sudden switch before they were ready to support it internally. However, we were able to accelerate the overall rollout curve, compressing it from an originally planned couple of months down to a few weeks.

The planned slow, highly coordinated release of the new design became a sprint to phase out the old design as rapidly as we could. It went more smoothly than we could have hoped, under the circumstances. The reaction was broadly positive, and people loved the new features. Our timing, uncanny as it was, couldn’t have been better.

We made a “We are the champions” thank you video for our customers who participated in the Slack Champions beta. Our team celebrated with a goofy, remote launch party. Popping champagne alone while on Zoom isn’t quite the same, but it felt good to reach our goal together.

Releasing our new design closed a chapter in Slack’s history. We had fully metamorphosed from a hungry, chaotic startup to a mature, confident public company. The redesign set the table for our next wave of product evolution. The pandemic became a catalyst for what would come next for our company and our business.

The long road

The office closure announced in March dragged into months. In June, Robby Kwok, our SVP of People (and later Chief of Staff to the CEO) announced that we would be deferring any decision on office reopening until at least September 2020. The intention was to provide clarity to everyone working from home that they would be there for at least the summer. This gave parents a chance to plan their summer with some certainty, while avoiding setting any timelines that we couldn’t commit to with any confidence.

This was one of Stewart’s leadership strengths: if a decision is needed but impossible to make with the current information, make the smallest decision possible in the moment and set a date for re-evaluation.

Robby also took the opportunity to share that Slack would be paying salaries for furloughed in-office workers through the end of the year:

We know that any changes we make to our offices, especially phasing out or significantly curtailing in-office amenities, will impact not only our employees but the network of contractors and vendors whose hard work supported Slack’s food and beverage programs, social gatherings, and more. This is a responsibility we take very seriously, which is why we’re committing to pay all Slack contractors through the end of 2020.

We never went back to the old Vancouver office. And we never stepped foot in our new one. Ready for us to move in on April 1st, 2020, it instead sat pristine and untouched for two years, espresso machine ready and neon Slack sign on the wall, before it was eventually leased to another company.

Of course by then a lot of other things had changed.

Thanks to Jaime DeLanghe for her notes on this post. Thanks to Javier Turegano, Whitney Levine and Colm Doyle for sharing photos and images.