The Master Plan

Backstage, Stewart vibrated with his typical charismatic energy. An assistant checked his lapel mic. Everyone in the company, now numbering nearly 500 people in early 2017, awaited him. He was ushered on stage to enthusiastic applause from the crowd and expectant video participants from our offices around the world.

Slack's CEO had somehow managed to turn the few million dollars leftover from his second failed game into a multi-billion dollar company. Now he was going to present his vision for how Slack would make the leap from breakout success to a major player in the software industry.

Surprising everyone in our industry, team messaging software had become big business. And the biggest tech companies in the world had taken notice. Microsoft announced Teams as a direct response to Slack’s surging popularity, Google repositioned Hangouts as a Slack competitor (with a typically awkward name: Google Hangouts Chat), and Facebook launched Workplace as a company-focused “Facebook for the office”. We had established the market for our product. Now it was up to us to secure and maintain the lead in that market.

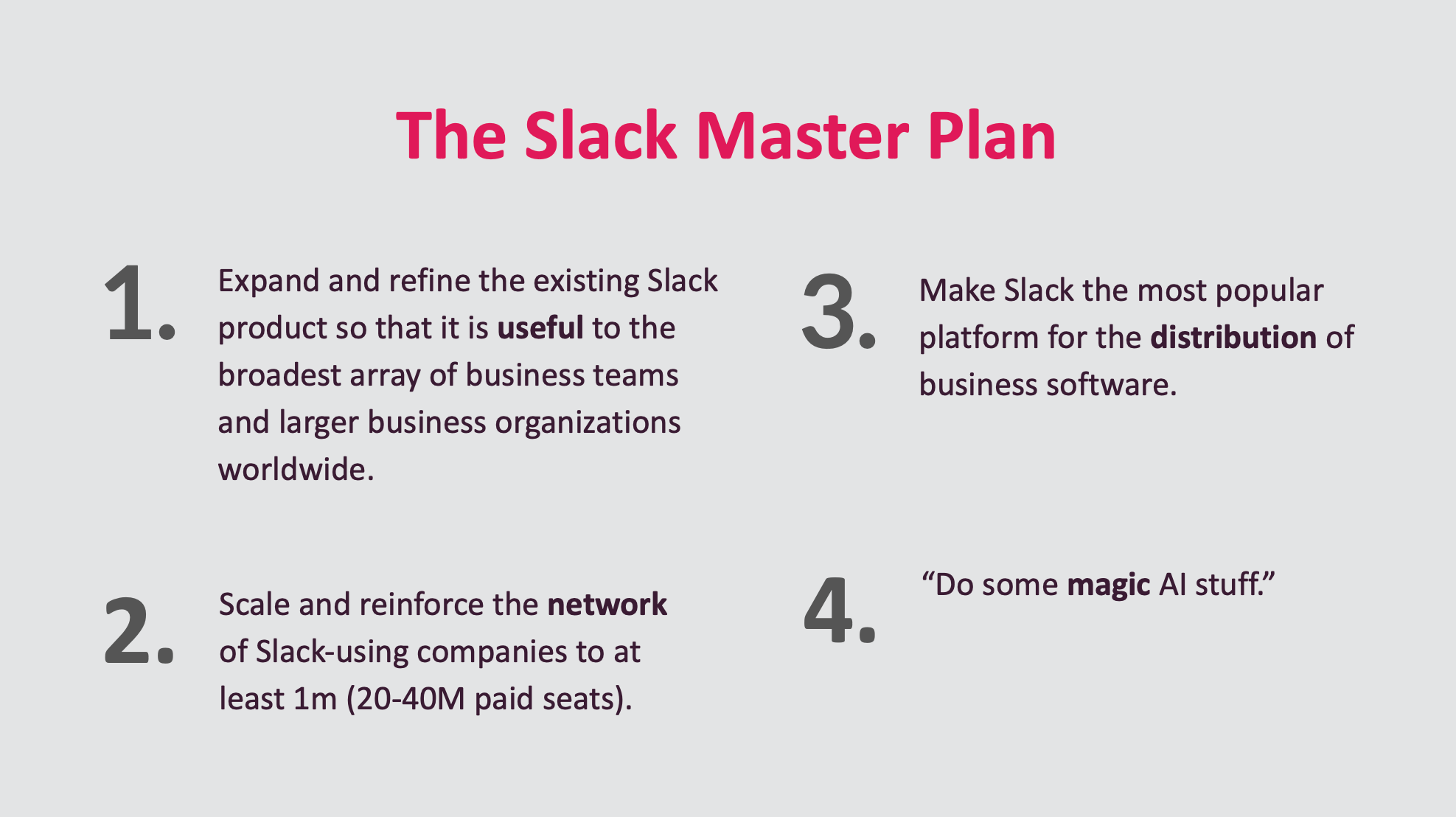

Stewart got right down to it. He projected one of his trademark hastily-assembled slides on screen:

The Master Plan

- Expand and refine the existing Slack product so that it is useful to the broadest array of business teams and larger business organizations worldwide.

- Scale and reinforce the network of Slack-using companies to at least 1m (20-40M paid seats).

- Make Slack the most popular platform for the distribution of business software.

- “Do some magic AI stuff.”

This one slide mapped out four major areas of effort. Each was already underway, with an associated department of the company established to tackle it. Internally, our names for these things were simpler:

- Enterprise (Grid)

- Shared Channels

- Platform

- Search, Learning & Intelligence (SLI)

Taken together, Stewart proposed, these would cement Slack’s early lead. They would allow us to address the larger and more lucrative Enterprise software market, establish a moat through the network effects of Shared Channels and Platform integrations, and tap into emerging trends around AI-driven insights into company data.

Enterprise Grid was a response to the scale of the companies that had begun using Slack. These customers, including some of the largest companies in the world, demanded a different set of product features than we had initially set out to build. As importantly, they expected a drastically different experience when it came to sales, support, and access to company executives. We were no longer selling Slack by credit card to small teams. We were negotiating 8-figure deals over multi-year terms with major Fortune 100 companies. We had to reorganize our company to support theirs, and build a product suitable to their complex needs.

Shared Channels would allow companies to connect their Slack workspaces together in specific channels. Though this sounded simple in concept, the hairball of considerations – from the lifecycle of shared channels, privacy of profile information, ownership of data, naming of shared objects, administrative permissions, all the way down to how custom emoji reactions would be shown across companies – was a nightmare of product complexity and engineering assumptions to untangle. But the promise of inter-company communication within Slack suggested a profound opportunity for us to build a true network product.

Platform had been an early driver of uptake among companies in tech and media. Our API and integrations allowed teams to plug in the data sources they depended on, and to take actions in other systems from within Slack. But there was a lot of latent potential in building deeper programmability and expressiveness into Slack’s message layer. And Stewart anticipated that, done right, Slack could become the interface to more of a company’s software systems – both for users and administrators.

SLI (Search, Learning & Intelligence) was tasked with doing “magic AI stuff”, as Stewart playfully put it. Slack search worked well enough, but we suspected there was huge upside in bringing more sophisticated methods of searching company archives and providing insights across them. At the time, this meant applying machine learning and algorithmic analysis to user signals in order to surface and summarize useful data. This team would make speculative bets about what might work in this area, and see which ones paid off.

Stewart elaborated the specific near-term goals he had in mind, with the addition of our efforts to make Slack a multilingual product for the first time:

Bring Grid to Market

We’ll build teams that can bring tens of thousands of users at our largest customers onboard in months instead of years.

Deliver on Platform Promise

We’ll extend our momentum with developers and invest in message interactivity, identity and app management to power more sophisticated workflows through Slack.

Shared Channels

We’ll begin to establish a network of Slack-using companies that can connect across organizational boundaries.

Internationalization

We’ll bring Slack to market in German, French, Spanish and Japanese, allowing both new payment methods and new currencies.

The audience of employees – live in San Francisco and remote in Vancouver, Dublin, and our newly opened Melbourne and New York offices – digested this vision. None of it was new, exactly. In some cases teams had been working in these areas for nearly a year by this point.

But taken together the ambition and scope of the vision was clear. We had to do all these things well and we had to do them quickly. The initial years of adoring press coverage and snowballing growth had evolved into a sharper-edged challenge. We found ourselves with aggressive competition and higher expectations, not to mention the pressure of our skyrocketing valuation.

Additionally, we needed to evolve the organization of the company to match our new goals. This meant more teams outside of what had historically been called Core Product. It meant more coordination across those teams. It meant trying to adapt the spark of Slack's magic into new and unforeseen shapes. It meant change.

Stewart finished his pitch with a simple reminder of our basic strategy:

Deliver a service that people love

Develop and scale a sustainable business

Hire great people and empower them to do their best work

Without any further ceremony, Stewart finished his presentation. The crowd slowly ebbed out of the All Hands space and off of the video call, back to their laptops and whiteboards.