Going Public – Part One

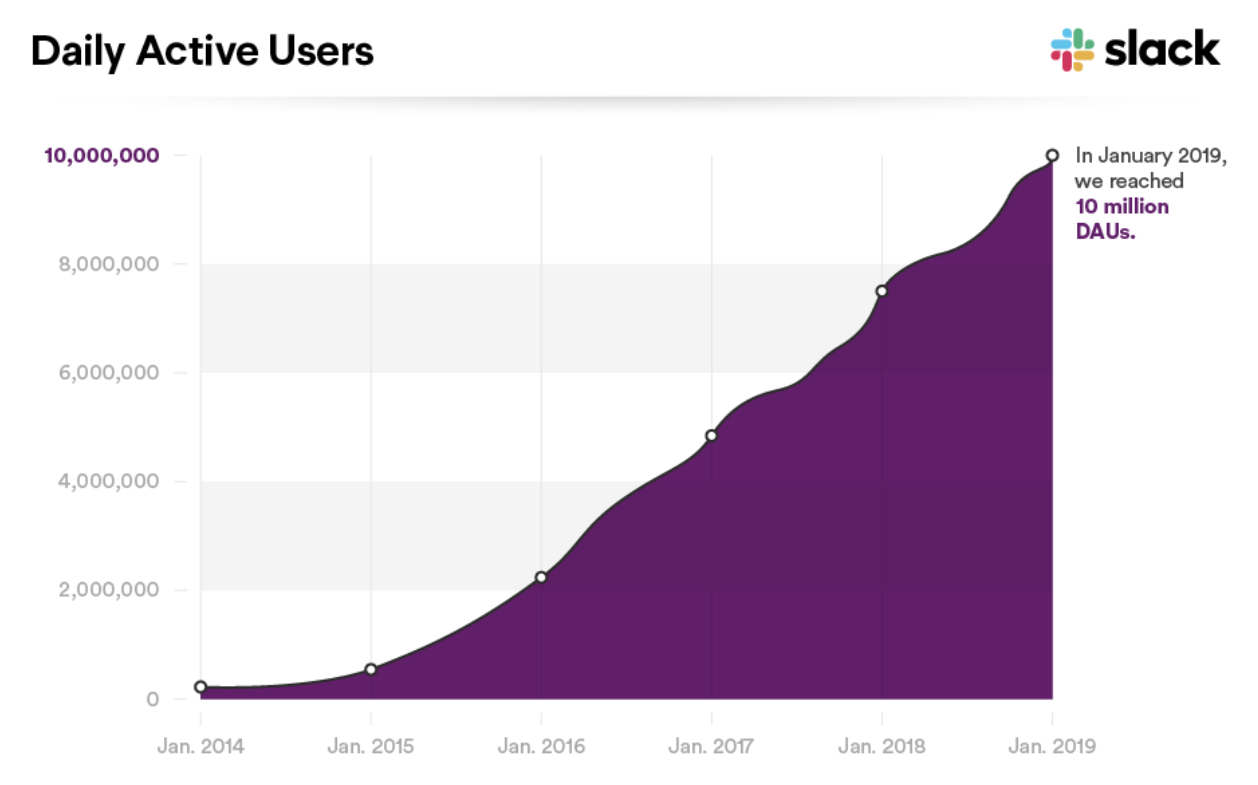

On April 26th, 2019, Slack filed to take the company public. We’d managed to overcome the most painful growing pains of scaling the company from a fledgling startup to a large, well-funded corporation spread around the globe. Miraculously, we crossed the chasm from early adopters and small businesses to enterprise customers, and had a thriving two-sided business of self-serve teams and sales-supported enterprise organizations. We were holding our own against Microsoft for the time being. Earlier that year, we surpassed 10 million daily active users and $400 million in annual recurring revenue.

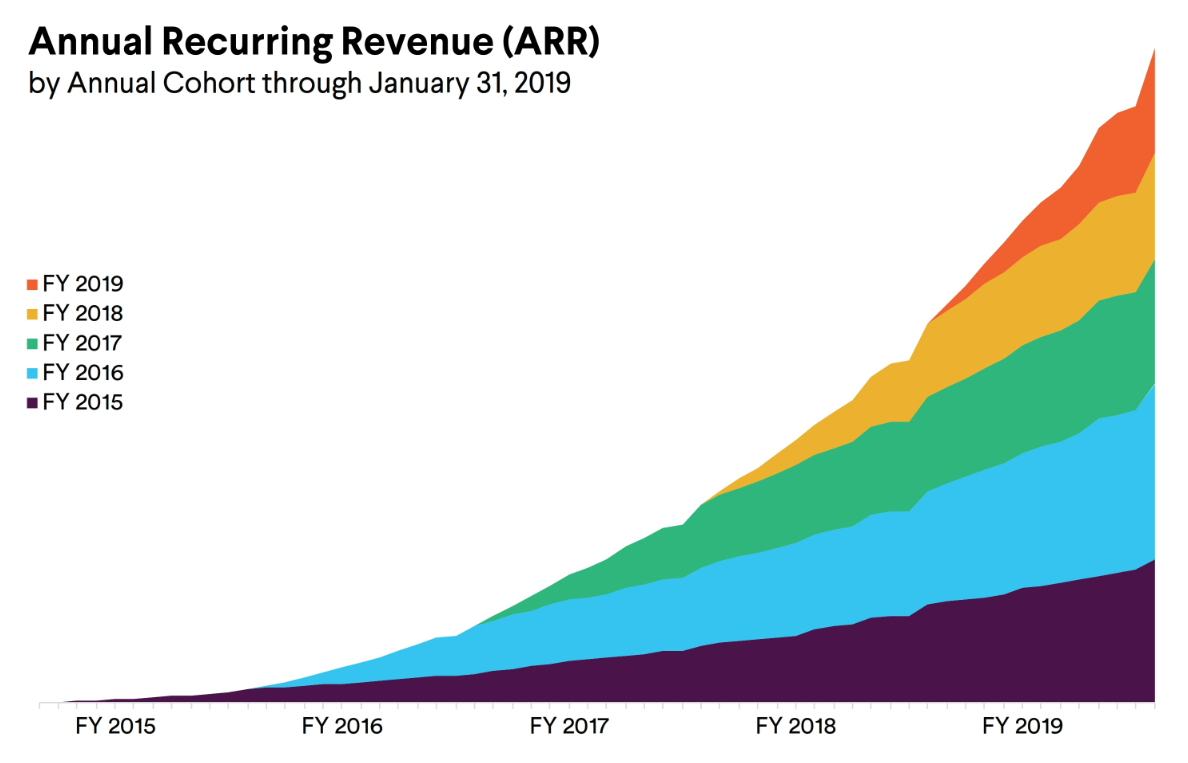

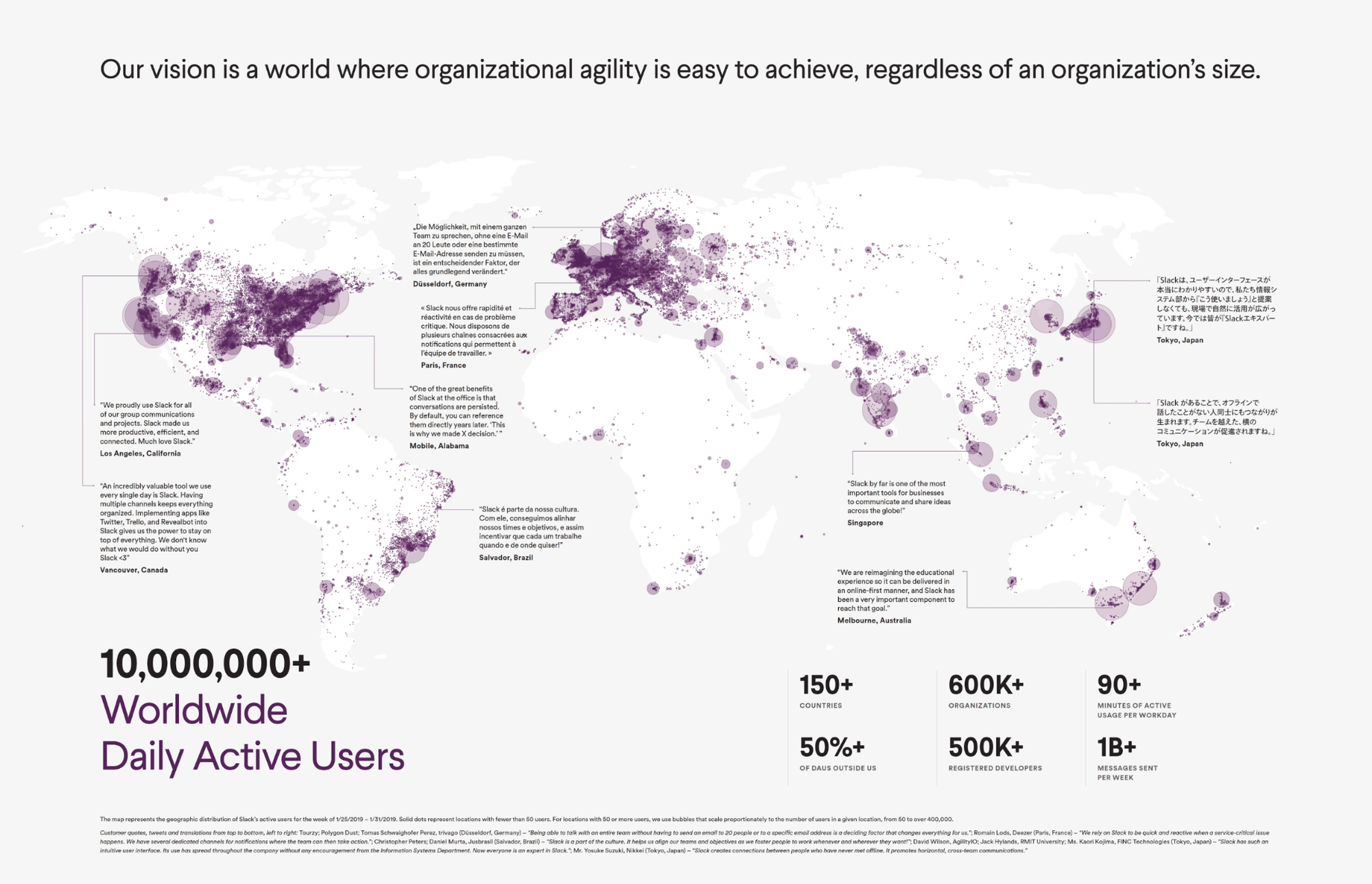

Graphs of revenue and user growth from our S-1 filing.

The summit of the mountain we’d been climbing since 2012 was in sight. No longer a hazy far-off possibility that we might one day reach, but a tangible event to work toward.

But boy did we have a lot of work to do to push for that summit.

Why go public?

Taking a company public means listing shares for sale on a publicly traded stock exchange. From its inception to this point, Slack was private. The shareholders of the company were the founders, venture backers, and employees. Without a market for those shares, any equity remained tied up in the company. It was worth a lot on paper, but those who owned it couldn’t do anything with that value.

Going public offered an exit for those investors and employees. Once Slack was public, they’d be able to sell their shares and withdraw money from the value of the company. For investors, it would pay out their commitment and belief in us at a substantial multiple of their initial investment. It would allow them to reinvest in other companies, pay out their own shareholders, and would represent a feather in their cap. They’d picked a winner.

For employees, the ability to sell shares meant they could use the value they’d helped build to do things in their own lives: pay off debt, put a down payment on a house, or go on a vacation. Provide for their extended family. Quit and start a new company. This was the payoff for committing their professional careers to a startup rather than a lower-risk job at an established company. After all, most startups fail, and very few reach the point of going public. This was the moment when those who’d poured their effort and passion into making Slack successful could reap the benefit of all that growth.

There was a second important reason to go public. We were now earning a substantial portion of our revenue from enterprise customers. For those forward-looking organizations at the forefront of evolving their work practices and technology, Slack was a perfect fit. But there were many others who were slower to adopt new technology, and more dubious about betting on an upstart company. Going public would establish a degree of reassuring credibility with many potential customers. It would indicate to the market and the world that we were here to stay, and that we could be trusted with their business.

Public readiness

Internally, nearly every aspect of the company and business needed work before we were ready to take it public. We had grown organically from a tiny startup to a big company. Once public, we’d be subject to a degree of scrutiny and attention that required different processes and expectations than we were used to.

Our financial team under CFO Allen Shim had been at this for several years already. The goal had always been to go public, and they’d reorganized our internal processes to make sure our financial reporting and business metrics would meet the bar expected of public companies.

The numbers looked very good. Our revenue had doubled each year from $105.2M in 2017 to $400.6M in 2019. We were not yet profitable, but this was a result of investing in growth and expansion during this period – a typical approach for fast-growing software businesses. Moreover, we had a war chest of $793M in cash, ready to continue that growth and providing a buffer against any unforeseen shocks.

From a competition standpoint, we’d outlasted our precursors and smaller competitors. Facebook Workplace and Google Hangouts had not made much of a dent in the market and, after an initial push, had been deprioritized by those companies. It was down to us and Microsoft Teams.

A new set of executive leaders was recruited to join the company and lead alongside Stewart and Cal. Many had taken previous companies public. They brought the experience and maturity that we needed, and also signaled the company’s coming-of-age to the market.

The herd of unicorns

The market itself was running hot. We were one of the so-called herd of unicorns going public that year – tech companies worth $1 billion or more.

- Lyft debuted in March at a $24 billion valuation

- Zoom went public in April at a $9.2 billion valuation

- PagerDuty went public in April at a $1.8 billion valuation

- Pinterest went public in April at a $12.7 billion

- Uber went public in May at an $82.4 billion valuation

The enthusiasm for high-growth tech businesses was at an all-time high, as was the market itself. The decade from the bottom of the global financial crisis in 2009 to 2019 was the longest bull run in history, with the market growing 330% in that time. Our timing was good.

But the stakes were high. WeWork was valued at $47 billion shortly before filing for its IPO later in 2019. Upon disclosing their financials, their valuation collapsed and the CEO stepped down in disgrace. We knew we didn’t have any skeletons lurking in our closet that could result in that kind of outcome, but we also knew that markets are not always rational in how they react to private companies going public.

Zoom’s stock popped 80% on opening day as demand outpaced expectations for what was essentially “better video calls”. Uber’s stock closed down nearly 8% on its first day despite its IPO being hotly anticipated. We needed to button up every facet of our business to make sure our debut was a success, or at least ensure that the things in our control were ready.

The rebrand

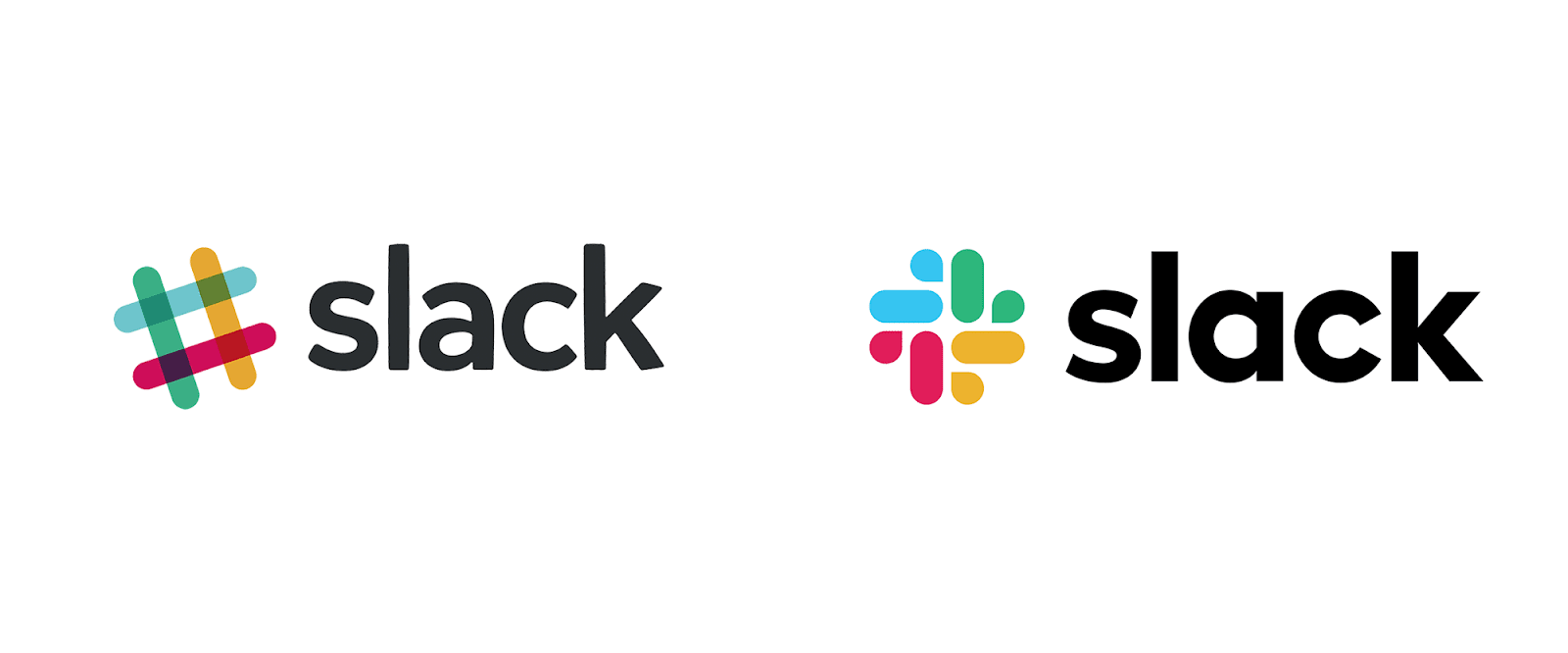

One piece of housekeeping that became apparent during this period of public readiness was the need to clean up our brand. Slack’s visual identity had become haphazard. Our multicoloured logo and plaid texture were not particularly consistent. Our type treatment was idiosyncratic. You couldn’t call our homegrown branding refined, nor could we count on customers recognizing it when they saw it.

We went to the professionals. Michael Bierut at Pentagram took on the project and worked directly with Stewart. The result was an evolution of our hashmark that streamlined and brightened the colour palette and tightened up the lettering. They recognized the value in refining rather than replacing the hash logo, and in maintaining the distinctive “aubergine” purple used in our apps as a brand element.

Overall, the work achieved exactly what was needed to elevate and rationalize our visual identity ahead of our debut. A dedicated internal team scoured our apps, websites and marketing, updating everything and revealing the new brand to the world in January 2019. They even coordinated to have all the external signage at our offices replaced on the same day we rolled it out.

People hated it. Was it four rubber ducks sniffing each other’s butts? A “whimsical swastika”? It looked too much like Google Photos. It looked like Microsoft’s logo. It looked like a health insurance company. It looked too moist. It had lost its soul.

Of course, people love to hate on the internet, and there’s nothing like a rebrand to draw out the trolls. They weren’t all wrong. But Stewart pegged the reaction, and was proven right in the long run. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

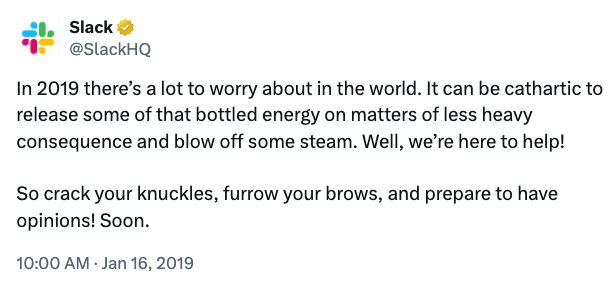

Our comms team anticipated that people would have opinions on the new logo. Stewart knew it would blow over quickly.

Engineering readiness

From 2014 to 2019 we scaled the service up through exponential growth, recurrent outages and performance bottlenecks. We achieved the stability our customers expected, and could now confidently support the largest organizations in the world, and the web of network connections they were building between one another with Shared Channels.

After nearly two years of effort, we were also finally ready to release our completely rewritten desktop app. It was dramatically faster and used far less memory than our original version. For users it was a step change in terms of performance, with complaints about slowness dropping to a fraction after its release. Our workhorse client that users spent the majority of their time on got a big upgrade just in time for our debut.

For our engineering team, it was much easier to build features on the new version. The codebase had also been rationalized in a way that made everything more sensible and easier for new engineers to learn. It remains the basis of today’s desktop and web clients six and a half years later.

Across every facet of our services and apps, our engineering team had risen to the challenge of our rapidly growing business. Through many ups and downs, we had built a service that could scale to the biggest companies in the world and serve Slack reliably 24/7 around the globe.

Some of Slack's beautiful offices in Tokyo (top left), Melbourne (top right), Dublin (bottom left), and Vancouver (bottom right).

Global expansion

Supporting and selling Slack around the world meant working where our customers were. Slack started with offices in Vancouver and San Francisco. Over the years we expanded to New York, Dublin, Melbourne, Toronto, Denver, and London. In 2018, after acquiring Astro, we opened an office in Pune, India. Early in 2019 we opened a stunning office in Tokyo. It mattered to have our people in the timezones where our customers were, and for our salespeople to speak their languages. With these additions we became a truly global company and workforce.

This was accompanied by expanded localization of our apps. In September 2017 we launched support for UK English, French, German, Spanish, and Japanese. We would go on to add Latin American Spanish, Italian, Brazilian Portuguese, Korean, and Chinese (both simplified and traditional). Beyond localizing the interfaces in our product, we also added support for these languages on our website and help center. Taken together, these languages represent roughly half of the world’s population, and the majority of business customers.

The S-1

When a company files to go public, they publish an S-1. This is a document registered with the SEC in the US that details a company’s financials, business arrangements, risks and outlook. It discloses the nitty-gritty details of a company’s internal workings for investors to dissect and evaluate ahead of going public.

Much of what goes into an S-1 is required and formulaic. Companies have to adhere to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) standards for financial statements. However, in tech there are often different approaches to recognizing revenue than in other industries, and different expectations around profits and losses for a high-growth company.

Our finance team needed to explain and account for our annual recurring revenue based on our subscription model, and explain our high investment in R&D and growth via marketing and sales spend. In traditional industries, these expenditures and methods of accounting for income might look suspicious. In high-growth software companies they are taken for granted, but still need to be explained. We also had to explain how we categorized types of users, how we measured churn and expansion in our customer base, and how our freemium model worked. It was our job to educate investors about the kind of business we were running, and why it was worth investing in.

Moreover, Stewart wanted to use our S-1 as a vehicle to tell Slack’s story. It was not in his nature to submit a business word salad, even if the document would mostly be read for the financial tables. He insisted on writing the prose himself, and his fingerprints are obvious in the result:

We needed a new way to work that would help us make the most of both our people and our significant investment in software. What was available was incomplete, inadequate, and unfit for our work at hand. What we needed did not exist. So we built it.

Since our public launch in 2014, it has become apparent that organizations worldwide have similar needs, and are now finding the solution with Slack. Our growth is largely due to word-of-mouth recommendations. Slack usage inside organizations of all kinds is typically initially driven bottoms-up, by end users. Despite this, we (and the rest of the world) still have a hard time explaining Slack. It’s been called an operating system for teams, a hub for collaboration, a connective tissue across the organization, and much else. Fundamentally, it is a new layer of the business technology stack in a category that is still being defined.

The most helpful explanation of Slack is often that it replaces the use of email inside the organization. Like email (or the Internet or electricity), Slack has very general and broad applicability. It is not aimed at any one specific purpose, but nearly anything that people do together at work.

Stewart enumerates that Slack is for “accountants, customer support reps, engineers, lawyers, journalists, dentists, chefs, detectives, executives, scientists, farmers, hoteliers, salespeople, and many others.” Detectives, dentists and farmers!

In typical fashion, Stewart avoids the jargon, hype and empty business-ese that usually fill such documents. Instead, he tells the story of why we built Slack, why it’s important, and how it represents a rare transformation for how companies operate.

How many CEO’s have the humility to say they don’t quite know how to explain their product? Stewart somehow managed to turn this ambiguity into a compelling narrative about Slack’s value.

Quiet period

When the S-1 was filed in April, we entered what’s known as a quiet period. Having shared our public documentation about the business, we were required to restrict further communication to investors to avoid unfair disclosure of material non-public information that might influence them. This meant we had to be circumspect about any outward communication from the time we filed our intent to list until listing day.

This was unfamiliar territory for us: Slack as a company had always been transparent and forthcoming about what we were working on, new customer stories, and speculative feature releases. But it was an important aspect of complying with the requirements laid out in federal securities law.

Unfortunately, shortly after filing, one of the directors on our board gave an interview on CNBC. In it, Chamath Palihapitiya, who ran Social Capital and owned about 10% of Slack through venture investment, praised Slack and Stewart, and hyped the upcoming listing – comparing us to Zoom which had just had a hugely successful IPO, and to Facebook where he had been an executive. Though he didn’t disclose any new information, his position of access to the company made these statements verboten.

In response, Slack had to submit a follow-up to our filing:

The statements made by Mr. Palihapitiya and the other persons in the interview do not reflect the Company’s views and are not endorsed or adopted by the Company. The Company specifically disclaims the statements made by Mr. Palihapitiya in the interview. Further, the Company notes that Mr. Palihapitiya made several statements in the interview that could be understood to imply or suggest a comparison between the Company and other high-profile public companies and the Company disavows any such comparisons, whether intentional or unintentional.

Fortunately, the SEC was mollified by our response, and did not delay our listing. Just a bump in the road – if a rather high-stakes one – on our journey to the mountaintop.

Crisis avoided, we were all set. We would take the company public on the NYSE on June 20th, 2019.

Stay tuned for Going Public – Part Two about listing day, coming soon.